HREC Director of Education Speaks to Students at New Jersey Catholic High School About the Holodomor

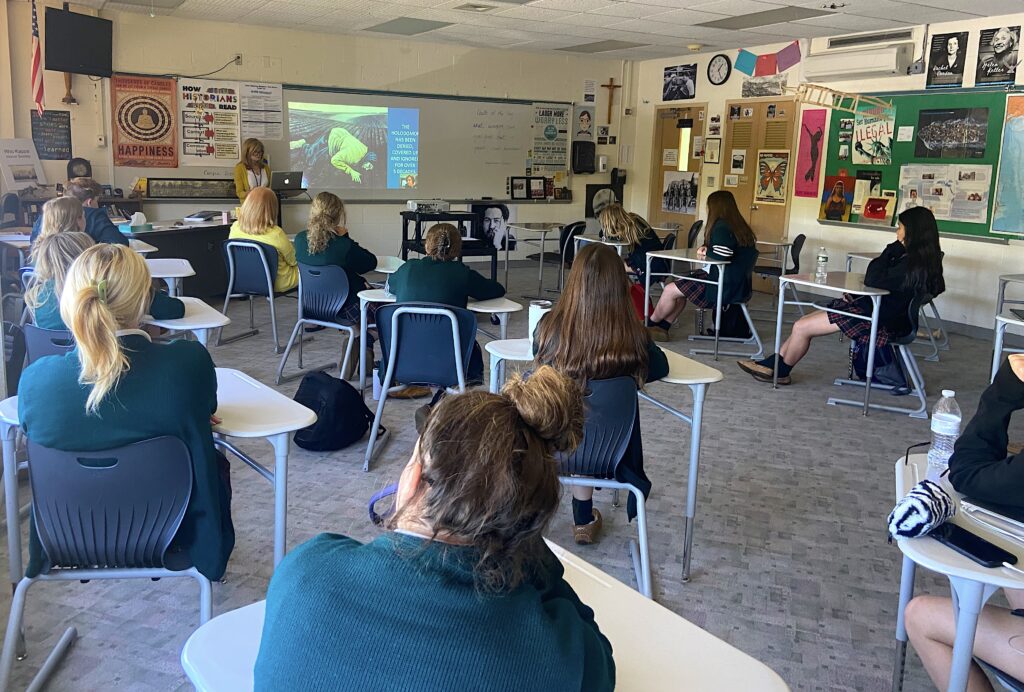

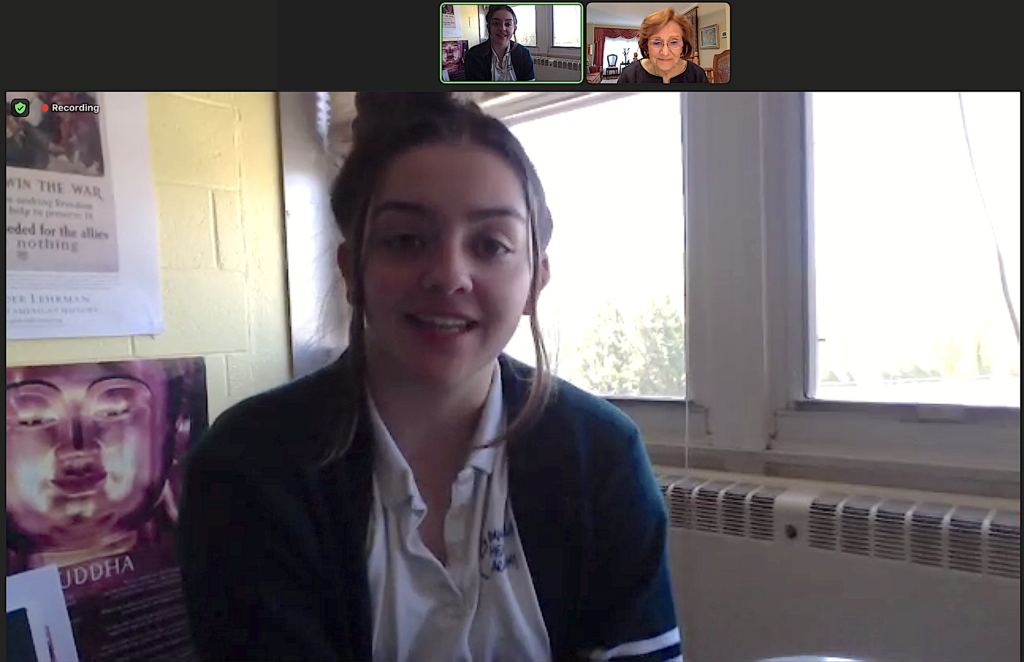

On 10 May 2022, Valentina Kuryliw, the Director of Education of the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium was an invited Guest Speaker via Zoom to educator Dr. Sue Kenney’s “Genocide and Film” class at the Immaculate Heart Academy Catholic High School in the Township of Washington, New Jersey, USA. Kuryliw was asked to speak about the personal experiences of her survivor parents and other family members during the deliberate mass starvation of the Ukrainian people in the 1932-1933 Holodomor in Ukraine. The all-girls school students had been taught about the history of the Holodomor and looked forward to listening to a child of two survivors speak. Parental permissions were given for recording and photographing the session.

Kuryliw talked about how 31% of those who brutally starved to death during the Holodomor were children, the 5 basic stages of human rights abuse that lead to genocide, the UN Convention’s Article 2 and intent in genocide, why certain people are targeted in genocide, the importance of eyewitness survivor testimonies, her own family history and birth in a Displaced Person’s camp in Germany after WW2. Her family, like so many others at the time, survived life under 2 totalitarian regimes and the death of many Ukrainians under both.

She spoke also about the men in her family. Her father Ivan’s history of being arrested as the son of a kulak, being thrown out of school in grade 3 because “kulaks don’t need an education,” and being sent to the Belomorkanal labour camp to build the canal between the White Sea and the Baltic Sea by hand in Russia’s far NW where he slaved until summer’s end in 1932. After this he was frequently surveilled, arrested and in and out of prison for years. Her grandfather Karpo was arrested in 1928 for being opposed to collectivization, his store was confiscated, since he was considered an “enemy of the people” as a kulak, and he perished in prison in 1937. His wife Ulyana was thrown out of their home in the winter of 1930 with her 5 children. The neighbours were forbidden from helping her or her children. Valentina’s mother Nadia was 11 at the time of the Holodomor. Her mother Tatiana worked in the kolhosp (collective farm) from dusk to dawn. Her husband Semen was a carpenter who worked in the local distillery that produced alcohol–the distillery never lacked for rye grain during the Holodomor. He repaired all the machinery there. Every day the discarded chaff from the fermented grain was thrown into a large pit outside the distillery that Kuryliw’s grandmother would painstakingly collect daily, wash, dry and grind to turn it into a kind of bread to eat. Kuryliw also recounted some of her mother’s memories from the Holodomor. Because her grandfather ended up with pneumonia and was the only one that could repair all the machinery, his family received a sack of grain and a sack of sugar from the state, which helped keep the family alive during the worst period of starvation in 1933.

Kuryliw also spoke about the cover-up and denial of the Holodomor by western journalists like Walter Duranty, and about western governments who ignored the situation and did not want to be involved. She spoke about Raphael Lemkin, the grandfather of the term “genocide,” and about James Mace’s contributions in revealing the truth about the Holodomor. And she spoke about Russia’s current war against Ukraine and Putin’s stated genocidal intentions for the imaginary and so-called “denazification” of the majority of the Ukrainian people, about the mass civilian burial sites in Irpin, the use of filtration camps and the “re-education” of the remaining survivors in Ukraine. Valentina Kuryliw suggested students use the UN Convention on the Punishment and Prevention of the Crime of Genocide (1948) and compare what happened in the 1932 Holodomor to what is happening in today’s genocidal Russian war against Ukraine.

Kuryliw concluded by discussing American aid, social justice and what we as citizens of democracy can do in the ongoing global fight for democracy. Students asked questions afterwards about how the legacy of the Holodomor has affected Valentina on a personal level generationally, about how things work in a totalitarian system, and about the changing world order.

Video