ULEC Interview with Valentina Kuryliw

Loading...

Loading...

Source: ULEC

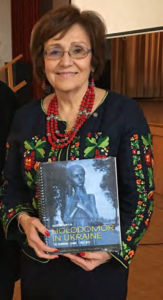

Valentina Kuryliw (Валентина Курилів)

Educator and Department Head of History and Social Studies in the secondary school system in Ontario for over 35 years; now retired.

UCC National Holodomor Education Committee, Chair (2009- present)

HREC – Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, Director of Education (2013-present), a project of CIUS at the University of Alberta

UCRDC – Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre, Holodomor Committee, Member of the Board (2011-present )

Valentina Kuryliw is a retired department head of history and social studies and a history teacher with over 35 years of teaching experience at the secondary school level in school systems in Ontario. She is the daughter of two Holodomor survivors. Since her retirement, Kuryliw has advocated for the Holodomor, the Ukrainian genocide of 1932-1933, to be included in the Ontario school curriculum and across Canada with the inclusion of a special Holodomor Memorial Day to be commemorated in schools on the fourth Friday in November.

Retirement has not slowed her down. She is currently the Chair of the National Holodomor Education Committee of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (2009- present), the Director of Education for the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (HREC) at CIUS, University of Alberta (2013-present), and a Member of the Board of the Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre (UCRDC, 2011- present).

Valentina Kuryliw was born in 1945 [née Mychajlowska] in a Displaced Persons camp in Mannheim, Germany; the family immigrated to Canada in 1950. Both her parents survivied the Holodomor while her father was sentenced to the Bilomor Kanal concentration camp in the early 1930s. Her mother, Nadia Menko Mychajlowska, witnessed Stalin’s Communist regime taking away food and using the grain for alcohol in the local distillery while people were brutalized, killed and starved to death around her. “We came to Canada and landed at Pier 21 in Halifax. We have a bronze brick there for our family,” she states in a “Canada 150” article for the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. Her family lived in Montréal where she grew up in a parish of Ukrainian political émigrés. “Everyone there had a story to tell about what happened to them in Ukraine and growing up in that type of atmosphere you were saturated with the political, with the concept of injustice that permeated through all these peoples’ lives. It transferred to their children by osmosis,” Kuryliw says. The parishioners’ stories influenced Valentina to work on a history degree. “When we came to Canada, my father told us: ‘we don’t have a lot of money, but I’ll work my hands to a pulp if I have to, so that you get an education.’” Kuryliw went to McGill University and McArthur Teacher’s College, moved to Collingwood then Sudbury to teach, met her husband Ihor Kuryliw, and moved to Toronto where she taught history and social studies with the Toronto District School Board, and got involved in curriculum development.

Accomplishments

Thanks to Valentina Kuryliw’s activism and efforts over the past three decades, as of June 2015, the Holodomor now may be taught in at least 12 of 27 courses in the Ontario curriculum. Holodomor Memorial Day is also now officially acknowledged and commemorated in many schools on the 4th Friday in November in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Kuryliw has also changed how history is taught in Ukraine, where she has been presenting teacher training sessions for 16 summers with her ground- breaking course and her first textbook: Metodyka Vykladannya Istoryi / Methodology for Teaching History (2003, 2008 in Ukrainian). She received the Shevchenko medal from the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC) for education and is the recipient of the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Award for making a significant contribution to the development of Canada.

Kuryliw authored the founding lesson entitled “The Historian’s Craft Lesson on the Holodomor,” on the Holodomor Mobile Classroom of the Holodomor National Awareness Tour. Valentina Kuryliw’s article “The Ukrainian Genocide The Holodomor, 1932 – 1933: A Case of Denial, Cover Up and Dismissal” was published in genocide scholar Samuel Totten’s Teaching About Genocide: Insights and Advice from Secondary Teachers and Professors, Vol. 1 in the USA (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield publishers, 2018). Her second book, Holodomor in Ukraine, the Genocidal Famine 1932-1933: Learning Materials for Teachers and Students (Toronto: CIUS Press, 2018), was published as a resource for engaging students interactively in critical thinking about the Holodomor in curricula across Canada. It has also been used as a resource for Holodomor Teaching Guides in the state curriculum of several U.S. states. Kuryliw’s third and most recent book, The Historian’s Craft Lesson on the Holodomor, is an engaging sample lesson about the Holodomor which will be published by CIUS Press in late 2020.

Influence and Future Aspirations in this field

With HREC Education, Kuryliw has now held two National Holodomor Education Conferences (2013 and 2017); the most recent hosted 120 educators at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, MB. In 2016, HREC Education and affiliate HREC in Ukraine signed an agreement with the Ministry of Education and Science in Ukraine to set up a Methodology Lab on teaching the Holodomor in Ukraine and to hold an annual summer school for educators from across Ukraine. In 2018, Kuryliw also instituted the HREC Educator Award for Holodomor Lesson Plan Development, a prize of $2,000 CDN in 2021. Her book on the Holodomor has been translated into Ukrainian and should be available at the beginning of 20121. Plans for the French translation of the Holodomor in Ukraine are also set for publication in 2021.

FUN FACTS about Valentyna Kuryliw

Valentina loves to sing, and opera is a beloved hobby. She says, “I have sung in many different choirs and choral groupings (duet, trio, quartet).”

“I’m a world traveller and love hiking, especially in the Alps with my husband.”

“I’ve been an activist since I was a teenager in the ODUM youth group. In university, I helped organize demonstrations, became involved in the Ukrainian response to the Deschênes Commission (The Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals in Canada), I was Vice President of the Canadian Ukrainian Immigrant Aid Society and the President of the Canadian Ukrainian Opera Association.”

Why did you become an educator?

Why did you become an educator?

I love to teach students and others about the unknown or forgotten topics in history. I was a real storyteller.

Why did you choose to study history?

I needed to know more about my family history and the influences of the past on the present.”

Why are you passionate about the Holodomor?

“I am the daughter of two Holodomor survivors. I felt the pain of my parents against the wall of silence about even bringing up the topic of the Holodomor in relation to other genocides. This was something that was not being discussed. Why was it being ignored, denied and covered up? I wanted to give voice to it, and as an educator I felt I had the knowledge and the teaching skills to do so.

What makes you tick?

I get upset with issues of social injustice and feel that human rights need to be addressed constantly. I’m also always interested in culture, my own and others. I feel that to understand and have an appreciation for other peoples’ cultures you have to understand and know your own.

What are your favourite moments as a teacher?

What are your favourite moments as a teacher?

I love to see my students demonstrate that they have learned something, that I can actually see it in action. And also, I’m always happy to see my students entering into the teaching profession. I’ve had students talk to me years later to tell me what influence I had on their lives.

What makes you feel like you had a ‘good day’ at school?

A “good day” at school for me is when students stop me in the hall or at lunch and tell me that it was a great class.

This article was also researched, compiled and written by Sophia Isajiw, Research Associate, HREC.