Gareth Jones – The first western journalist to describe the Soviet Ukrainian famine — the Holodomor — as a man-made famine

Gareth Jones

The first western journalist to describe the Soviet Ukrainian famine — the Holodomor — as a man-made famine. He is often referred to as a ‘Hero of Ukraine.’

GARETH JONES

1905-1935

“Russia is in a very bad state; rotten, no food, only bread; oppression, injustice, misery among the workers and 90% discontented…

The winter is going to be one of great suffering there and there is starvation. The government is the most brutal in the world. The peasants hate the Communists.”

~ GARETH JONES

August 26, 1930

Gareth Vaughan Jones Papers, National Library of Wales, Folder 16 (Letter to his family written from Berlin after he got out of Russia)

WHO

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones (1905-1935) was a Welsh journalist. He spoke five languages. For a time, he was a private secretary and researcher to the former Welsh Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Lloyd George (from 1930-31 and 1932-33). Jones was intellectually inquisitive by nature. At the age of 27, he courageously undertook a forbidden and dangerous journey on foot through the Soviet countryside, risking arrest, deportation and death while crossing alone from Russia into Ukraine in March of 1933. His direct eyewitness testimonies, which are written in straightforward reporting, revealed to the world the scale and atrocity of Stalin’s Soviet regime’s mass starvation of its Ukrainian citizens in 1932-1933. His notebook diaries are filled with direct statements from Ukrainian and Russian villagers which he later quoted in his newspaper articles.

Gareth Jones was born in Barry, Wales. His mother, Annie Gwen Jones, spent three years (1889-1892) working in Hughesovka, modern day Donetsk, in eastern Ukraine. She was a tutor to the granddaughters of 19thC Welsh engineer John Hughes who founded the city of Donetsk (originally in 1869 named “Hughesovka/Yuzovka” after him and renamed “Stalino” in 1924 after Stalin). His mother’s unpublished memoir and stories likely inspired him to visit the Soviet Union, particularly Ukraine. Gareth was a brilliantly perceptive and keenly curious young man who graduated with a first-class Honours degree from Cambridge, England and began work as Foreign Affairs Advisor to former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Jones was fluent in Welsh, English, French, German and Russian.

After a period of working as a foreign advisor for the public relations agency Ivy Lee and Associates in New York (1931-1932), Jones returned to work for Lloyd George again before travelling in Europe to write as a freelancer. In 1933 he started on the editorial staff of the Western Mail newspaper on contract. He travelled to Russia by train on a visa he received as the former PM’s private secretary, arriving in Moscow on 5 March 1933. With this and an invitation from the Consulate of Germany in Kharkiv, it was easier to obtain an agreement from the Soviet Foreign Ministry to travel further by train from Moscow to Kharkiv – then the capital of Soviet Ukraine. But Jones quietly disembarked about 40 miles north of Kharkiv. Jones was a walker, and he courageously set out on a difficult and dangerous solo trek by foot from Soviet Russia into Soviet Ukraine. He was intent on obtaining firsthand quotes to back up the rumours of famine he had heard from speaking to agricultural experts in London in October of 1932. He broke the story of the famine taking place, particularly horrific in Soviet Ukraine, to the world in a Berlin press conference on 29 March 1933. Over the next month he published five main articles drawing heavily on what he had witnessed in Soviet Ukraine and the situation in the USSR. Jones probably paid with his life for accurately reporting the horrors of the Holodomor and painstakingly documenting the truth denied and covered up by Stalin and many in the West. Gareth Jones was murdered in Inner Mongolia under strange and suspicious circumstances by bandits on 12 August 1935, the day before his 30th birthday. The two men who helped him arrange his trip had connections to the Soviet secret police.

WHAT

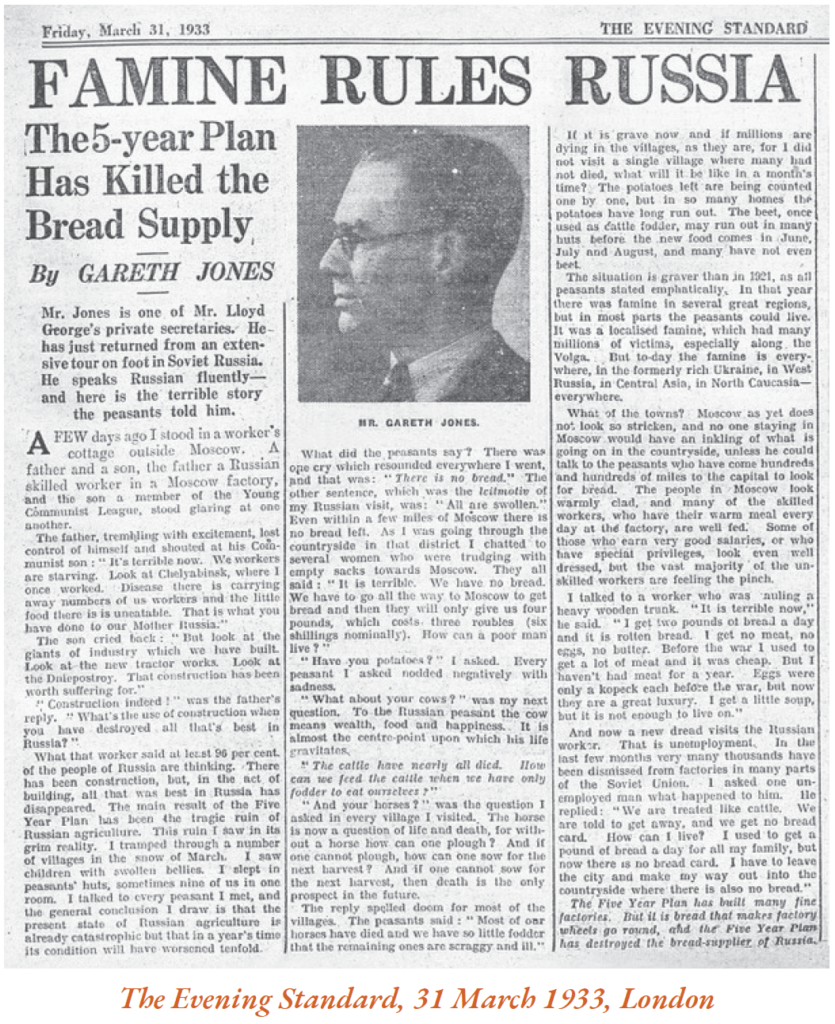

By early spring 1933, the Soviet regime had imposed a ban on foreign journalists traveling to areas affected by famine. But the fact that famine was raging in Soviet Ukraine was common knowledge in Moscow among foreign diplomats and journalists. Defying the Soviet authorities in March of 1933, Jones left his train in the afternoon of March 11th and immediately began talking to locals in the Black Earth district. He walked into Ukraine on the 12th and into Kharkiv on the 13th, walking at least 40 miles through some 20 villages and 12 collective farms talking to people, recording their voices directly in his notebook diaries, sharing food he had brought in his backpack, and sleeping on the floor of their homes. Through his written diaries about the starvation that he witnessed and directly recorded firsthand, Jones gave a voice to the farmers and villagers whose voices were being silenced by the Soviet regime, thus keeping their experiences alive and authentic. His writings provide primary source evidence derived from diary notes, newspaper articles, and personal correspondence. Jones was appalled by what he witnessed and was unafraid of speaking truth to power. After several days in the German Consulate he returned to Moscow, then left the Soviet Union for Berlin on March 29th, where he issued the press release published by many newspapers (“Famine Grips Russia, Millions Dying”) in which he wrote: “Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread; we are dying.’ This cry came to me from every part of Russia*.” For this he was immediately attacked by Walter Duranty, the Moscow bureau chief of The New York Times, who infamously denied there was any famine in Ukraine. Because Jones defied Soviet propaganda and wrote truthfully about what he had witnessed firsthand, the Soviet authorities accused him of espionage, banned him from the Soviet Union, and the Soviet secret police blacklisted him. The Soviet Union denied, covered up and ignored the Holodomor, and Russian leaders continue doing the same today. The Holodomor claimed at least 4 million lives, of which 31% were children under the age of ten.

By early spring 1933, the Soviet regime had imposed a ban on foreign journalists traveling to areas affected by famine. But the fact that famine was raging in Soviet Ukraine was common knowledge in Moscow among foreign diplomats and journalists. Defying the Soviet authorities in March of 1933, Jones left his train in the afternoon of March 11th and immediately began talking to locals in the Black Earth district. He walked into Ukraine on the 12th and into Kharkiv on the 13th, walking at least 40 miles through some 20 villages and 12 collective farms talking to people, recording their voices directly in his notebook diaries, sharing food he had brought in his backpack, and sleeping on the floor of their homes. Through his written diaries about the starvation that he witnessed and directly recorded firsthand, Jones gave a voice to the farmers and villagers whose voices were being silenced by the Soviet regime, thus keeping their experiences alive and authentic. His writings provide primary source evidence derived from diary notes, newspaper articles, and personal correspondence. Jones was appalled by what he witnessed and was unafraid of speaking truth to power. After several days in the German Consulate he returned to Moscow, then left the Soviet Union for Berlin on March 29th, where he issued the press release published by many newspapers (“Famine Grips Russia, Millions Dying”) in which he wrote: “Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread; we are dying.’ This cry came to me from every part of Russia*.” For this he was immediately attacked by Walter Duranty, the Moscow bureau chief of The New York Times, who infamously denied there was any famine in Ukraine. Because Jones defied Soviet propaganda and wrote truthfully about what he had witnessed firsthand, the Soviet authorities accused him of espionage, banned him from the Soviet Union, and the Soviet secret police blacklisted him. The Soviet Union denied, covered up and ignored the Holodomor, and Russian leaders continue doing the same today. The Holodomor claimed at least 4 million lives, of which 31% were children under the age of ten.

New York Times journalist Walter Duranty wrote a deceitful article on March 31, 1933, entitled “Russians are hungry but not starving,” to which Gareth responded in The New York Times: “Wherever I was in Russian* villages, I heard the moan, ‘No bread, we are dying.’”

* The USSR was widely referred to at that time simply as ‘Russia.’

After returning to Britain, Gareth Jones wrote 21 articles about famine in the Soviet Union and what he specifically witnessed in Ukraine. These were all published between March 31st and April 20th, 1933.

“In one of the peasant’s cottages in which I stayed we slept nine in the room. It was pitiful to see that two out of the three children had swollen stomachs. All there was to eat in the hut was a very dirty watery soup, with a slice or two of potato, which all the family – and in the family I included myself –ate from a common bowl with wooden spoons. Fear of death loomed over the cottage, for they had not enough potatoes to last until the next crop. … I set forth again further towards the south and heard the villagers say, “We are waiting for death.”

- “Nine to a Room in Slums of Russia: Russia’s Collapse,” The Daily Express, April 6, 1933: www.garethjones.org/margaret_siriol_colley/The%20exhibition/nine_room.htm

WHEN

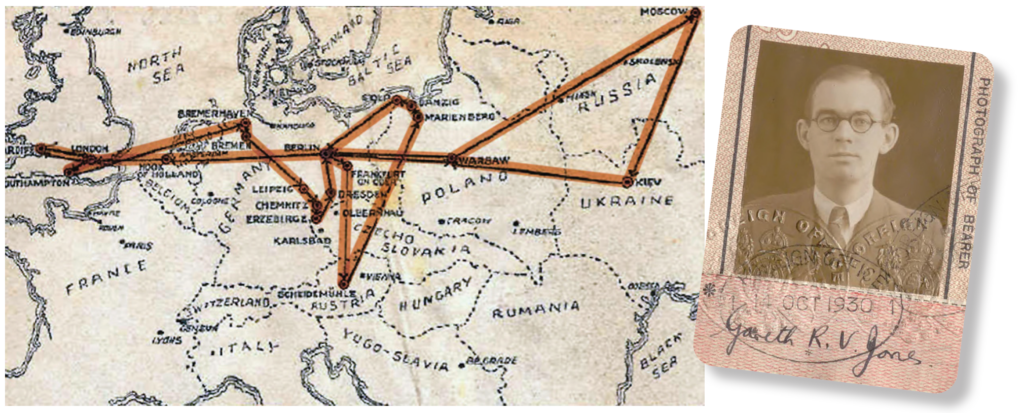

Jones visited the Soviet Union three times from 1930-33 (August 1930, August 1931, March 1933) and after each visit wrote articles for various newspapers about the conditions he witnessed resulting from Stalin’s Five-Year Plan for industrialization. His first brief pilgrimage to Ukraine at the age of 25 in August of 1930 was undertaken to keep Lloyd George informed about what was happening there. These reports were published in the London Times as “An Observer’s Notes.” In the autumn of 1931, he visited the USSR again with Jack Heinz (of Ketchup family fame), this time while working for the Ivy Lee and Associates agency. He published some of his articles from this trip under his own name. He made a third and final visit to the USSR in March of 1933, which he financed himself, and which provided the evidence for his exposé of the Holodomor in Berlin. Gareth Jones earned a solid reputation for integrity because of the honesty with which he tried to get to the bottom of all information – and the truth.

WHERE

As his Moscow train drew close to the Ukrainian border near Kharkiv, Jones jumped off to continue his journey on foot. He saw the Russian side of the border was experiencing famine conditions, but in Ukraine he witnessed far worse and more deadly conditions. Walking through villages and collective farms just before the peak of the famine, sharing his food with the starving people, listening to their stories, and watching how desperately they scraped for food, Jones recorded each detail in his notebooks as it happened. He spoke with ordinary farmers who were regular peasants, and not considered to be “kulaks,” (or so-called, ‘wealthier farmers’).

In a letter to the editor of the Manchester Guardian newspaper on May 8th, Jones wrote: “…in almost every village, the bread supply had run out two months earlier, the potatoes were almost exhausted, and there was not enough coarse beet, which was formerly used as cattle fodder, but has now become a staple food of the population, to last until the next harvest.” “In each village I received the same information – namely that many were dying of the famine and that about four-fifths of the cattle and the horses had perished. One phrase was repeated until it had a sad monotony in my mind, and that was: “Vse pukhli” (“all are swollen, i.e., from hunger”), and one word was drummed into my memory by every talk. That word was “golod,” meaning “hunger” or “famine.” Nor shall I forget the swollen stomachs of the children in the cottages in which I slept.”

www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/peasants_in_russia.htm

Map showing Gareth Jones’ travels in Central Europe on the tour

he has been describing in the Western Mail & South West News.

WHY

As Jones stated in his 1933 Berlin press release: “I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia* and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.”

By taking initiative and journeying through the Russia-Ukraine borderlands, Jones saw firsthand the difference in conditions in both countries. He testified that the famine he witnessed was not a natural disaster and that the government’s “murderous terror” and policy of collectivisation and peasant resistance to it were part of the causes. A few months before Jones’ trip to Ukraine as famine worsened in December 1932, Stalin launched a major attack targeting Ukrainian language, culture, and identity itself. Jones’ journey took place prior to the deadliest months of the Holodomor – the death toll in Ukraine reached its peak in June of 1933.

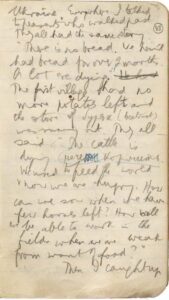

Explore Gareth Jones’ diaries online at The National Library of Wales: www.library.wales/garethvaughanjones

GJ Soviet Diary 1 (4-10 March 1933) Page 92

(Gareth Vaughan Jones Papers B1/15)

https://bit.ly/3SRzkkc

QUOTES

“I tramped for several days through villages in the Ukraine and there was no bread there, many children had swollen stomachs, nearly all the horses and cows had died, and the people themselves were dying. The terror has increased tremendously and the G.P.U. [secret police] has almost full control.”

— Gareth Jones

letter to family from Danzig, Sunday March 27, 1933

“There is no bread. We haven’t had bread for over 2 months. A lot are dying.” The first village had no more potatoes left and the store of beetroot was running out. They all said: “The cattle is dying, there’s nothing to feed them with. We used to feed the world & now we are hungry.” … “We were the richest country in the world for grain. We fed the world. Now they have taken all away from us.”

— Gareth Jones

GJ Soviet Diary I (4 – 10 March 1933) Page 92 and 93, in Lubomyr Luciuk’s “Tell Them We Are Starving”: The 1933 Soviet Diaries of Gareth Jones Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2015

“Tell them in England. Starving. Bellies extended. Hunger.”

— Gareth Jones

GJ Soviet Diary 1 (4 – 10 March 1933) Page 90 (Gareth Vaughan Jones Papers B1/15)

“The period of the liquidation of the kulak has almost ended. The policy of the Communist Party has triumphed for they have crushed their enemies in the villages and 60 percent of the peasant households are now members of collective farms. The day of the individual farmer is over, and pressed by high taxes fearing least his house be taken away from him or dreading a hungry exile in Siberia, he becomes a member of a collective farm. He is dazed, his old life is shattered and he does not know what the future has in store. … Throughout Russia one hears the same tale: “They took away our cow. How can it get better if we have no land and no cow?” The cry of the Russian peasant has always been “Land and Liberty,” and it is the same cry today.”

— Gareth Jones

“The Real Russia: The Peasant on the Farm. Increase and Its Cost.” The Times, 14 October 1931

A street in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, was officially named after Gareth Jones on 31 July 2020.

“In the Ukraine, in one collective the ration was 20 lb. ‘The peasants complain: Come and see the grain, rotten grain: that is what they keep for us. All the best grain is sent to the nearest town for export, and we do not get enough to eat. Poor Mother Russia is in a sorry plight. What we want is land and our own cows.’ In some villages the government seizure of grain has led to fighting between the peasants and the Communist authorities.”

— Gareth Jones“

“The Real Russia: The Peasant on the Farm. Increase and Its Cost.” The Times, 14 October 1931

“Dear Mr. Lloyd George,

I have just arrived from Russia where I found the situation disastrous. The Five-Year Plan has been a complete disaster in that it has destroyed the Russian peasantry and brought famine to every part of the country. I tramped alone for several days through a part of the Ukraine, sleeping in peasants’ huts. I spoke with a large number of workers, among whom unemployment is rapidly growing. I discussed the situation with almost every British, German and American expert… The situation is so grave, so much worse than in 1921 that I am amazed at your admiration for Stalin.”

Gareth Jones’ letter to former British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George sent from Berlin on 27 March 1933

“He had the almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered.”

— Lloyd George

former British Prime Minister

“Gareth Jones had the courage to see for himself.”

—Timothy Snyder

contemporary historian

“For his courage he paid with his professional reputation.”

— James Mace

historian

RECOMMENDED ARTICLES

Written by Gareth Jones about the Holodomor

- Jones, Gareth. “Famine Rules Russia: The 5-Year Plan Has Killed the Bread Supply,” The Evening Standard, March 31, 1933.

www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/holodomor.jpg - Jones, Gareth. “There is No Bread: Gareth Jones Hears Cry of Hunger All Over Ukraine, Once Russia’s Sea of Grain. ”Sunday American/Los Angeles Examiner, January 13, 1935.

www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/hearst2.htm - Jones, Gareth, “Famine grips Russia Millions Dying. Idle on Rise, says Briton.” New York Evening Post, Night Edition, front page, March 29, 1933.

www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/millions_dying.htm - Jones, Gareth, Complete articles on Soviet Ukraine (at that time referred to as “Russia”):

www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/soviet_articles.htm

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ABOUT GARETH JONES

- Applebaum, Anne. “How Stalin Hid Ukraine’s Famine from the World,” The Atlantic, October 13, 2017.

www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/10/red-famine-anne-applebaum-ukraine-soviet-union/542610/ - Bukovksyi, Serhii (Bukovsky, Sergey). The Living (Zhyvi), film documentary, 2008.

https://youtu.be/1lDp9AMACys - Colley, Margaret Siriol and Nigel Linsan Colley. More than a Grain of Truth: The Official Biography of Gareth Jones. London: Lume Books, 2020.

www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0845RPRCF - The Gareth Jones Website (constructed by his family to honour his career)

www.garethjones.org - The National Library of Wales resources (including digitised copies of his diaries and correspondence)

www.library.wales/garethvaughanjones - Mace, Dr. James. “A Tale of Two Journalists: Walter Duranty and Gareth Jones.” ukrweekly.com, New Jersey: The Ukrainian Weekly, No. 46, November 16, 2003, Pp. 5&8 (accessed 5 August 2021).

www.ukrweekly.com/archive/pdf3/2003/The_Ukrainian_Weekly_2003-46.pdf - Gamache, Ray. Gareth Jones: Eyewitness to the Holodomor.Cardiff: Welsh Academic Press, 2018.

- Luciuk, Lubomyr, “Tell Them We Are Starving”: The 1933 Soviet Diaries of Gareth Jones. Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2015.

- Shipton, Martin. Mr. Jones, The Man Who Knew Too Much: The Life and Death of Gareth Jones. Cardiff: Welsh Academic Press, 2022.

When reading Jones’ articles, and those by other journalists of this time period, it is important to note that:

- The term Holodomor was not used commonly until later decades, people said “the holod” or “famine.”

- At the time of Gareth Jones’ writings, central and eastern Ukraine were under the rule of the USSR–the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics under the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin and his Communist regime. It was common usage among journalists, politicians and most academics in the 1930s and after to refer to Ukraine as “Russia” and use the Russian spellings of Ukrainian city names since this was an expectation of Soviet officials and because much of Ukraine had been part of the Russian Empire prior to 1917. Ukraine also came to be referred to as “the Ukraine” in Jones’ writings and in the West at this time. It was part of Stalin’s intent to eradicate individual national identities to create a single Soviet identity using Russian language, culture and identity interchangeably.

Please be aware of these as you read the articles.

Use for educational purposes. Other reprints by permission of the author.